Consider the amount of plastic you put into the trash or recycling on a typical day. There's the lid to your coffee cup, and perhaps a bag from a newspaper. There's the wrapper from a granola bar, a yogurt container, a salad clamshell, and the plentiful packaging from inside a box that arrived in the mail.

Many of these plastic items are useful and convenient, but they also come with a high environmental cost. In 2016, the U.S. generated more plastic trash than any other country—46.3 million tons of it, according to a 2020 study published in Science Advances. That's 287 pounds per person in a single year. By the time these disposable products are in your hands, they've already taken a toll on the planet: Plastics are mostly made from fossil fuels, in an energy-intensive process that emits greenhouse gases and creates often hazardous chemicals.

And then there's what happens when you throw them away.

If you're like most people, you probably assume that when you toss plastic into the recycling bin it will be processed and turned into something new.

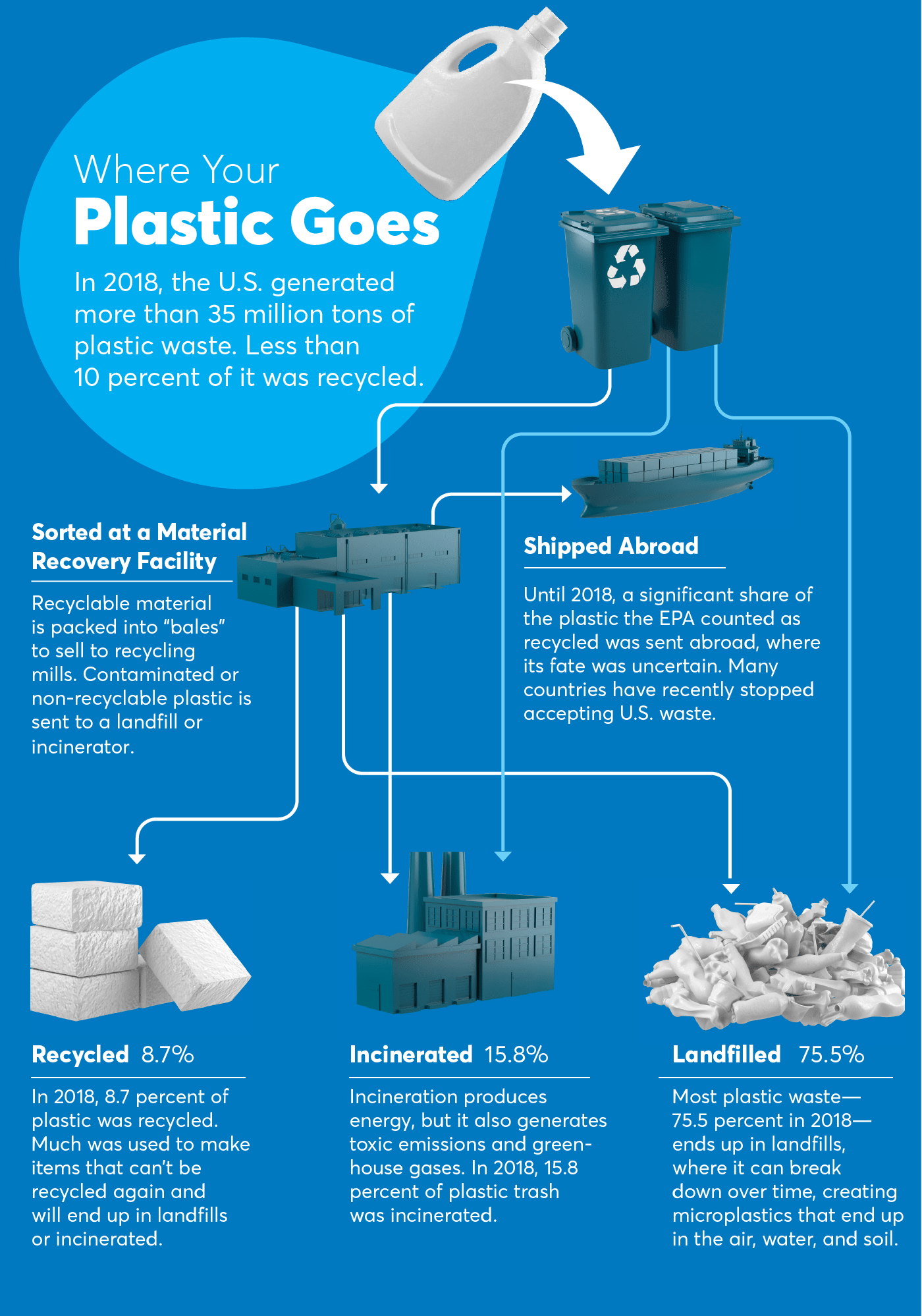

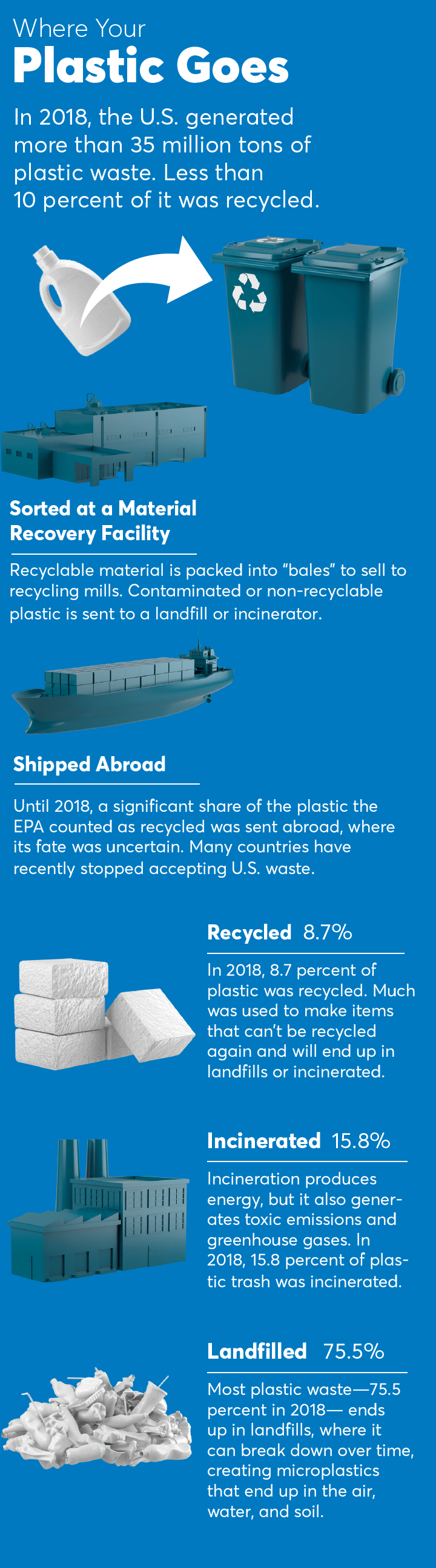

The truth is that only a fraction of plastic is actually recycled. According to the most recent data estimates available from the Environmental Protection Agency, just 8.7 percent of the plastic that was discarded in the U.S. in 2018 was recycled.

The popular perception that plastic is easily and widely recycled has been shaped by decades of carefully calculated messaging designed and paid for by the petroleum and gas companies that make most of that plastic in the first place, and the beverage companies that depend on plastic to bottle their products.

"Recycling is sold as a means of not worrying about the problem," says Judith Enck, a former regional administrator at the EPA, now a visiting professor at Bennington College in Vermont and president of Beyond Plastics, a group focused on ending plastics pollution. The companies paying for the ads that frame recycling as an easy solution to a potentially devastating environmental problem know that recycling cannot keep up with the flood of new plastic, Enck says.

One of four things happens to plastic after you're done with it. If it's not recycled—and it's usually not—it is landfilled, incinerated, or littered. The EPA estimates that in 2018, about 16 percent of U.S. plastic waste was incinerated. A relatively small amount was littered. Most of the rest ended up in landfills—including a lot of the plastic people dutifully put into recycling bins.

Over decades or even centuries, much of that littered and landfilled plastic breaks down into tiny particles known as microplastics, which contaminate our food, the air, and water. They also accumulate in our bodies, potentially increasing our risk of chronic inflammation and other ills.

Experts say that while cutting back on plastic use is a worthy individual goal (see "How to Quit Plastic"), the only way to stem the rising tide of plastic is for companies to make less of it and for recycling programs to be retooled so that more of what we throw away is actually turned into something useful.

There's little to suggest this will happen anytime soon. Plastic production is expected to more than double by 2050, and even if it doesn't, the plastic trash that people continue to throw away will still have to go somewhere.

Find out how to quit plastic with tips from CR on ways to reduce this kind of waste and its environmental impact.

The Truth About Plastic Recycling

Dedicated bins for plastic waste are a common sight, and plastic recycling is widely promoted. So why does only a fraction of the plastic we toss actually get recycled?

One reason is that most plastic isn't easily recyclable, says Jan Dell, a chemical engineer who heads up The Last Beach Cleanup, a nonprofit focused on plastic pollution. Plastic products are often made of mixtures of many chemicals, which can stymie recycling processes by making it harder to isolate a base material that can be recovered and reused.

Perhaps the most important reason is that there is very little financial incentive to recycle: It's far less expensive to manufacture most types of plastic from scratch than it is to recycle old plastic into something new. The least recyclable plastic products include many labeled with the numbers 3 through 7 in the recycling triangle, as well as the majority of plastic bags and packaging film.

Certain types of plastic, however, are economically viable and relatively easy to recycle, and even in high demand. These include PET plastic bottles, like the ones soda and water are sold in, and HDPE milk jugs (respectively labeled with a number 1 or 2 inside the recycling triangle). But just 29 percent of the plastic used in these jugs and bottles was recycled in 2018.

According to guidelines from the Federal Trade Commission, at least 60 percent of Americans should have access to a program that recycles a particular item before it can be labeled as recyclable without some language noting that access to recycling may be limited. But these guidelines are rarely followed, according to a 2020 report from Greenpeace. (The FTC did not respond to a request for comment.)

Only numbers 1 and 2 bottles and jugs are recycled consistently; labeling other items as "check locally" inside a recycling triangle is just greenwashing, Dell says—a way for a company to imply that something will be recycled when it will almost certainly end up in a landfill.

Well-intentioned consumers are also partly responsible for the low plastic recycling rate. "Wishcycling," or tossing every type of plastic into the recycling bin and hoping for the best, can make separating out useful material more difficult and actually reduce the amount of plastic that is recycled, says Jeff Donlevy, the general manager at a California recycling facility who has been in the industry for more than 25 years. This can lead to recyclable plastic ending up in landfills and incinerators.

In theory, sorting plastics and depositing only readily recyclable types into the recycling bin would help fix this problem. (According to a May 2021 nationally representative survey of 2,079 U.S. adults by CR (PDF), 65 percent of Americans say they typically separate plastics for recycling.) But U.S. recycling trends have worked against this type of careful sorting. Many municipalities have switched to single-stream recycling, in which aluminum cans, glass bottles, plastic jugs, and paper and cardboard all get dumped into the same bin. That can make things easier for the consumer, but it also makes sorting out the recyclable plastic more difficult, so more ultimately ends up discarded rather than recycled, says Brandon Wright, vice president of communications for the National Waste & Recycling Association.

On the bright side, most discarded plastic bottles are collected and recycled in states that require people to pay a bottle deposit. But only 10 states currently have such laws.

Burning Questions

Until 2018, the U.S. shipped as much as half of its plastic recycling abroad, mostly to China and Hong Kong (where it was not always recycled). Tired of dealing with contaminated plastic bales that were largely waste, China in 2018 stopped taking all but the most pristinely sorted plastic. Other countries quickly followed suit. With fewer offshore disposal options, more and more plastic is piling up in the U.S., where it is landfilled or routed to municipal solid waste incinerators that burn non-recyclable plastics along with other trash to generate electricity.

Because it generates power, incineration can sometimes be framed as a form of renewable energy or reuse (the EPA describes it as "combustion with energy recovery"). But it is not clean energy.

Incineration of plastic in these facilities has led to a slight increase in greenhouse gas emissions in recent years, according to EPA data. Burning plastic also creates dioxins and furans, two types of toxic chemicals that can spread through the air and contaminate food, water, and soil. Over time, inhaling these chemicals can increase cancer risk, according to Marilyn Howarth, MD, an occupational and environmental medicine physician at the University of Pennsylvania.

What's more, incinerators are often situated in poorer communities that already have a high burden of air pollution from sources such as heavy industry and transportation. Residents of these areas face health concerns, including cardiovascular disease, childhood asthma, exposure to carcinogenic pollutants, and preterm births, according to a 2019 report published by the New School's Tishman Environment and Design Center, with support from the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA). About 4.4 million people in the U.S. live within a 3-mile radius of an incinerator, according to that report.

The plastics industry has proposed alternatives to incinerators and landfills. One breaks down plastic into a type of fuel; others use a chemical process to separate plastic into its component chemicals, which could then be used to make new plastic products. But these alternatives are not likely to solve the plastic problem anytime soon.

One assessment of an advanced plastic-to-fuel recycling process, commissioned by a plastic bag company, found that in some cases it could emit more greenhouse gases than landfilling or an incineration process.

In a statement, the American Chemistry Council, an industry group representing plastics manufacturers, said it expected such facilities—which are still relatively new—to operate more efficiently over time. Experts say that recycling with a chemical process is not economically viable because making new, virgin plastic from oil and gas is still much cheaper. "It fundamentally doesn't work," Enck says.

@consumerreports There's a big problem with plastic. But a cleaner future is possible, and you can help create it. #plasticpollution #climateaction #recycle #recycling ♬ original sound - Consumer Reports

A Cleaner Future?

From an environmental perspective, the biggest benefit of increasing the plastic recycling rate is not keeping plastic out of landfills or incinerators. "The value of recycling is displacing virgin production, because the amount of pollution generated when producing virgin materials is much greater than that generated when using recovered materials," says Reid Lifset, associate director of industrial environmental management at the Yale School of the Environment.

"Consumers really can change the market. Plastic companies are looking into better recycling methods because it is such an important consumer issue."

Shelie Miller, Phd, professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability

Legislative changes and consumer pressure could certainly create more of a market for at least some of the plastic that is now going straight into incinerators and landfills, says Wright, of the National Waste & Recycling Association. A legal requirement or company commitment to use more recycled material in plastic products, including those made of less frequently recycled plastics, could create incentives for manufacturers to make more recyclable products and for recycling facilities to do a better job sorting, processing, and actually recycling that material.

For example, the high demand for the type 1 plastic used in PET beverage bottles is largely due to consumers pressuring beverage companies to improve recycling processes and lawmakers requiring them to use a certain percentage of recycled plastic in their products. A California law passed last year, for instance, requires beverage bottles to be made of 15 percent recycled plastic. That will increase to 25 percent by 2025 and 50 percent by 2030. Requirements like these "force manufacturers to change the makeup of their products, to use more recyclable plastic or more environmentally friendly materials," says Shanika Whitehurst, associate director of product sustainability, research, and testing at CR.

"Consumers really can change and push a market," says Shelie Miller, PhD, a professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability. "Plastic companies are actively looking into better recycling methods and how to design plastics to be more easily recyclable because they know this is such an important consumer issue." The American Chemistry Council recently said it supports a national standard that would require all plastic packaging to contain at least 30 percent recyclable material by 2030.

Another part of the solution, according to Enck, Lifset, and others, is extended producer responsibility (EPR), which would require plastic makers and sellers to be responsible in some way for the life cycle of their products, including cleanup after they are sold. EPR usually involves producers either implementing collection programs themselves or funding local collection programs to ensure more products are recycled. An EPR system in British Columbia, for example, increased the share of plastic waste collected for recycling from 42 percent in 2018 to 52 percent in 2020.

In 2021, Maine became the first state in the U.S. to pass EPR legislation addressing packaging waste. The law will levy fees on companies that create or use packaging; fees will be lower for practices with less environmental impact, like using more recyclable materials. The fees will be used to fund local recycling efforts. Oregon passed an EPR law soon after Maine, and six other states have EPR bills in the works.

Enck says another worthy goal is eliminating single-use plastics, like plastic bags and polystyrene foam. But for such a change to have a positive impact, the items that replace them have to actually be reused—and often, says the University of Michigan's Miller. "Someone who goes to the grocery store and forgets to bring reusable bags and every time buys a new reusable bag is creating a more [harmful] single-use item," she says.

That suggests the real shift consumers need to make: More than just avoiding plastic, we need to evaluate our behavior and move away from unnecessary consumption and living a throwaway lifestyle. "If we're really honest, any solution will require us to analyze our own consumption to try to understand what we're consuming and why, and whether there are ways to reduce our individual consumption," Miller says. She acknowledges that's a tall order for a lot of people. It's much easier to say "I can consume anything I want. I'll just recycle it."

Editor's Note: This article also appeared in the October 2021 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.