Climate Change: Policy and Mitigation Factsheet

The Challenge

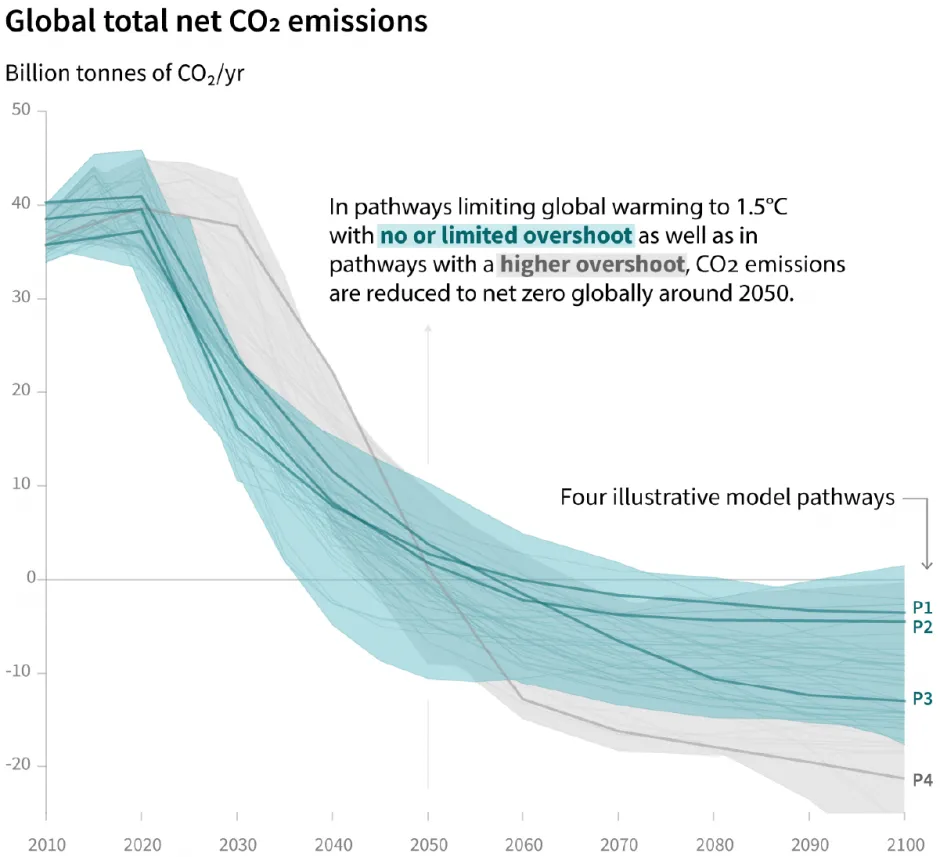

Climate change is a global problem that requires global cooperation to address. The objective of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which virtually all nations, including the U.S., have ratified, is to stabilize greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations at a level that will not cause “dangerous anthropogenic (human-induced) interference with the climate system.”1 Due to the persistence of some GHGs in the atmosphere, significant emissions reductions must be achieved in coming decades to meet the UNFCCC objective. In 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its Sixth Assessment Report. The report details the impacts of climate change and mitigation and adaptation strategies. To limit warming to 1.5oC based on 2019 emission levels, global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions need to be reduced by 48% by 2030 and reach net zero in the early 2050s, followed by net negative CO2 emissions. This requires deep and rapid emission reductions in all sectors.2 Current national targets under the Paris Agreement would lead to 52–58 billion metric tons or gigatons (Gt) CO2-equivalents (CO2e) per year by 2030—not enough to meet the 1.5oC target. 2018 GHG emissions were approximately 42 GtCO2 and would need to drop to between 25-30 GtCO2 per year by 2030 to remain on target.3 In 2021, U.S. GHG emissions were 6.3 GtCO2e.4

Carbon Emission Pathways to achieve 1.5oC Target3

General Policies

Market-Based Instruments

- Market-based approaches include carbon taxes, subsidies, and cap-and-trade programs.5

- In a tradable carbon permit system, permits equal to an allowed level of emissions are distributed or auctioned. Parties with emissions below their allowance are able to sell their excess permits to other parties that have exceeded their emissions allowance.5

- Market-based instruments are recognized for their potential to reduce emissions by allowing for flexibility and ingenuity in the private sector.5

Regulatory Instruments

- Regulatory approaches include non-tradable permits, technology and emissions standards, product bans, and government investment.

- In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that CO2 and other GHG emissions meet the Clean Air Act’s definition of air pollutants, which are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).6 After several appeals, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the ruling in 2012.7

- In the U.S., the Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) vehicles rule, administered by NHTSA, was implemented in 2020.8 NHTSA revised the SAFE standards in 2022, setting the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard to approximatly 49 mpg for passenger cars and light trucks by MY2026.9 The new CAFE standards are projected to reduce fuel use by more than 200 billion gallons through 2050, saving Americans money and cutting CO2 emissions by 2.5 Gt.10

Voluntary Agreements

- Voluntary agreements are generally made between a government agency and one or more private parties to “achieve environmental objectives or to improve environmental performance beyond compliance.”11 EPA partners with the public and private sectors to oversee a variety of voluntary programs aimed at reducing GHG emissions, increasing clean energy adoption, and adapting to climate change.12

The Kyoto Protocol

- The Kyoto Protocol came into force on February 16, 2005, and established mandatory, enforceable targets for GHG emissions. Initial emissions reductions for participating countries ranged from –8% to +10% of 1990 levels, while the overall reduction goal was 5% below the 1990 level by 2012. When the first commitment period ended in 2012, the Protocol was amended for a second commitment period; the new overall reduction goal is 18% below 1990 levels by 2020.13

The Paris Agreement

- In December of 2015, all Parties of the UNFCCC reached a climate change mitigation and adaptation agreement, called The Paris Agreement, in order to keep the global temperature increase (from pre-industrial levels) below 2°C.14

- The Paris Agreement entered into force on November 4, 2016. As of May 2023, The Paris Agreement had 198 signatories, 195 of which have ratified the agreement.15

Government Action in the U.S.

Federal Policy

- According to the U.S. Senate, “…Congress should enact a comprehensive and effective national program of mandatory, market-based limits and incentives on emissions of greenhouse gases that slow, stop, and reverse the growth of such emissions at a rate and in a manner that will not significantly harm the United States economy and will encourage comparable action by other nations…”16

- Due to the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008, large emitters of GHGs in the U.S. must report emissions to the EPA.17

- In 2023, the EPA proposed a new rule that would set limits for GHG emissions from power plants. This rule includes New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) and emission guidelines for new and existing fossil fuel plants.18

- In 2019, a Green New Deal resolution was introduced in the U.S. House. It proposed a 10-year mobilization effort to focus on goals such as net-zero GHG emissions, economic security, infrastructure investment, clean air and water, and promoting justice and equality.19

- In April 2021, President Biden held the Leaders Summit on Climate with 40 world leaders and announced the U.S. will “target reducing emissions by 50-52 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels.”20

- The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provides resources and loans to organizations including businesses, NGOs, and state, local, and tribal governments to accelerate the clean energy transition.21

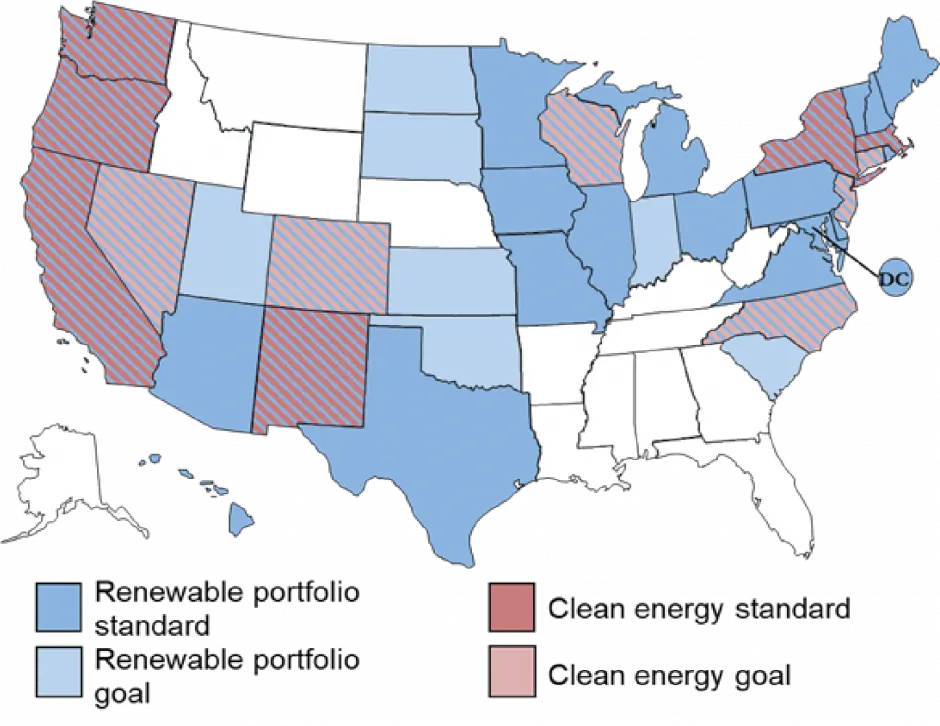

State Policy

- Climate change action plans have been released in 31 states and D.C. and 1 state is updating its plan.22

- Twenty five states and D.C. have GHG emissions reduction targets. California is targeting GHG emissions 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 and net zero CO2 emissions by 2045.23

- Twenty nine states, D.C., and three U.S. territories have Renewable Portfolio Standards, which specify the percentage of electricity to be generated from renewable sources by a certain date. Six states have Clean Energy Standards, which specify the percentage of electricity to be generated from low-to-no carbon sources and can include renewables, nuclear, and advanced fossil fuel plants with carbon capture and sequestration.24 A group of governors formed the U.S. Climate Alliance to achieve the GHG reductions outlined in the Paris Agreement. The alliance represents 54% of the U.S. population and 58% of the U.S. economy.25

States with Renewable and/or Clean Energy Standards24

Mitigation Strategies

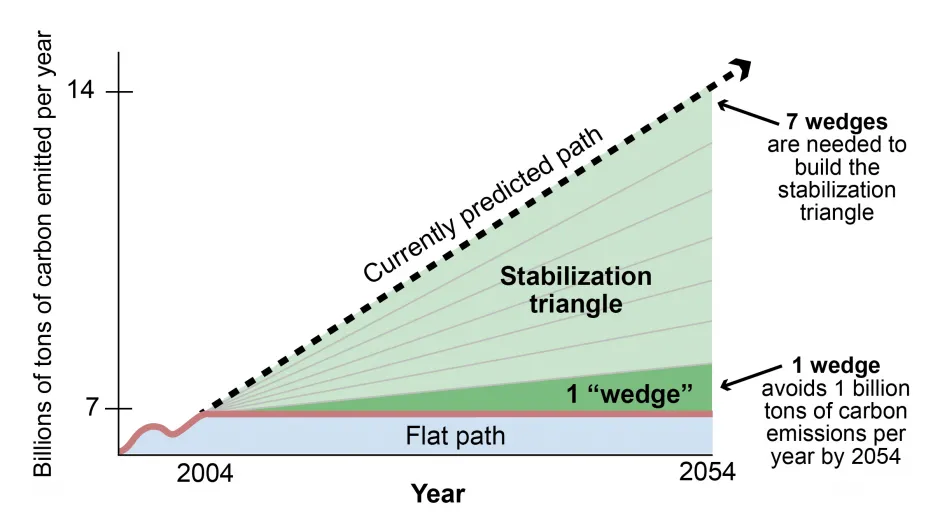

Stabilizing atmospheric CO2 concentrations requires changes in energy production and consumption. Effective mitigation cannot be achieved without individual agencies working collectively towards reduction goals and immense GHG emission reductions in all sectors.11 Stronger mitigation efforts require increased upfront investments, yet the global benefits of avoided damages and reduced adaptation costs exceeds the mitigation expense.2 Stabilization wedges are one display of GHG reduction strategies; each wedge represents 1 Gt of carbon avoided in 2054.26

Energy Savings: Many energy efficiency efforts require an initial capital investment, but the payback period is often only a few years. In 2016, the Minneapolis Clean Energy Partnership planned to retrofit 75% of Minneapolis residences for efficiency and allocated resources to buy down the cost of energy audits and provide no-interest financing for energy efficiency upgrades.27

Fuel Switching: Switching power plants and vehicles to less carbon-intensive fuels can achieve emission reductions quickly. For instance, switching from an average coal plant to a natural gas combined cycle plant can reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 50%.11

Capturing and Storing Emissions: CO2 can be captured from large point sources both pre- and post-combustion of fossil fuels. Once CO2 is separated, it can be stored underground depending on the geology of a site. Currently, CO2 is used in enhanced oil recovery (EOR), but longterm storage technologies remain expensive.28 Alternatively, existing CO2 can be removed from the atmosphere through Negative Emissions Technologies and approaches such as direct air capture and sequestration, bioenergy with carbon capture and sequestration, and land management strategies.29

Stabilization Wedges25

Individual Action

- There are many actions that individuals can take to reduce their GHG emissions; many involve energy conservation and also save money.

- Choose a fuel-efficient or electric vehicle. Decrease the amount you drive by using public transportation, riding a bike, walking, or telecommuting. For a 20-mile round trip commute, switching to public transit can prevent 4,800 lbs of CO2 emissions per year.30

- Ask your electricity supplier about options for purchasing energy from renewable sources.

- When purchasing appliances, look for the Energy Star label and choose the most energy efficient model.

- Energy Star light bulbs use ~90% less energy than standard bulbs, last 15 times longer, and save ~$55 in electricity costs over their lifetimes.31

- Space heating is the largest energy use in residential buildings (33%).32 Ensure that your house is properly sealed by reducing air leaks, installing the recommended level of insulation, and choosing Energy Star windows.33

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2023. "Climate Change: Policy and Mitigation Factsheet." CSS05-20.

References

- United Nations (UN) (1992) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

- U.S. EPA (2018) “2016 Climate Leadership Award Winners.”

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2018) Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5C

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2023) Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks 1990 - 2021.

- U.S. EPA (2001) The United States Experience with Economic Incentives for Protecting the Environment.

- Massachusetts, et al. v. EPA, et al. (2007) Supreme Court of the United States. Case No. 05-1120.

- U.S. EPA (2018) “U.S. Court of Appeals - D.C. Circuit Upholds EPA’s Actions to Reduce Greenhouse Gases under the Clean Air Act.”

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and U.S. EPA (2020) “The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule for Model Years 2021–2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks, Final Rule.” Federal Register, 85:84.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) (2022) Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards for Model Years 2024-2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks ; Final Rule. Federal Register, 87:84.

- U.S. Department of Transportation (2022) “USDOT Announces New Vehicle Fuel Economy Standards for Model Year 2024-2026”

- IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change.

- U.S. EPA (2021) “Clean Energy Programs.”

- UNFCCC (2020) “What is the Kyoto Protocol.”

- UNFCCC (2016) Summary of the Paris Agreement.

- UNFCCC (2023) Paris Agreement-Status of Ratification.

- U.S. Congress (2005) Energy Policy Act of 2005. 109th Congress.

- U.S. EPA (2017) “Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program.”

- U.S. EPA (2023) Greenhouse Gas Standards and Guildlines for Fossil Fuel-Fired Power Plants Proposed Rule Fact Sheet.

- The Library of Congress (2019) Bill Summary and Status 116th Congress, HR 109.

- The White House Briefing Room (2021) “Fact Sheet: President Biden’s Leaders Summit on Climate.”

- EPA (2023) “Summary of Inflation Reduction Act Provisions Related to Renewable Energy.”

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (2022) “U.S. State Climate Action Plans.”

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (2022) U.S. State Greenhouse Gas Emissions Targets.

- DSIRE (2022) U.S. Summary Maps: Renewable and Clean Energy Standards.

- United States Climate Alliance (2022) U.S. Climate Alliance Fact Sheet.

- Pacala, S. and R. Socolow (2004) Stabilization Wedges: Solving the Climate Problem for the Next 50 Years with Current Technologies. Science, 305: 968-972.

- U.S. EPA (2018) “2016 Climate Leadership Award Winners.”

- Kleinman Center for Energy Policy (2020) The Challenge of Scaling Negative Emissions.

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018) Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda.

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (2020) “Reducing Your Transportation Footprint.”

- Energy Star (2020) “Light Bulbs.”

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (2023) Annual Energy Outlook 2023.

- Energy Star (2022) “Seal and Insulate with ENERGY STAR.”