Greenhouse Gases Factsheet

The Greenhouse Effect

The greenhouse effect is a natural phenomenon that insulates the Earth from the cold of space. As incoming solar radiation is absorbed and re-emitted from the Earth’s surface as infrared energy, greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere prevent some of this heat from escaping into space, instead reflecting the energy back to warm the surface. Anthropogenic (human-caused) GHG emissions are modifying the Earth’s energy balance between incoming solar radiation and the heat released into space, amplifying the greenhouse effect and resulting in climate change.1

Greenhouse Gases

- There are ten primary GHGs; of these, water vapor (H₂O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) are naturally occurring. Perfluorocarbons (CF6, C2F6), hydrofluorocarbons (CHF3, CF3CH2F, CH3CHF2), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) are only present in the atmosphere due to industrial processes.3

- Water vapor is the most abundant and dominant GHG in the atmosphere. Its concentration depends on temperature and other meteorological conditions and not directly upon human activities.1

- CO2 is the primary anthropogenic greenhouse gas, accounting for 64% of the human contribution to the greenhouse effect in 2019.4

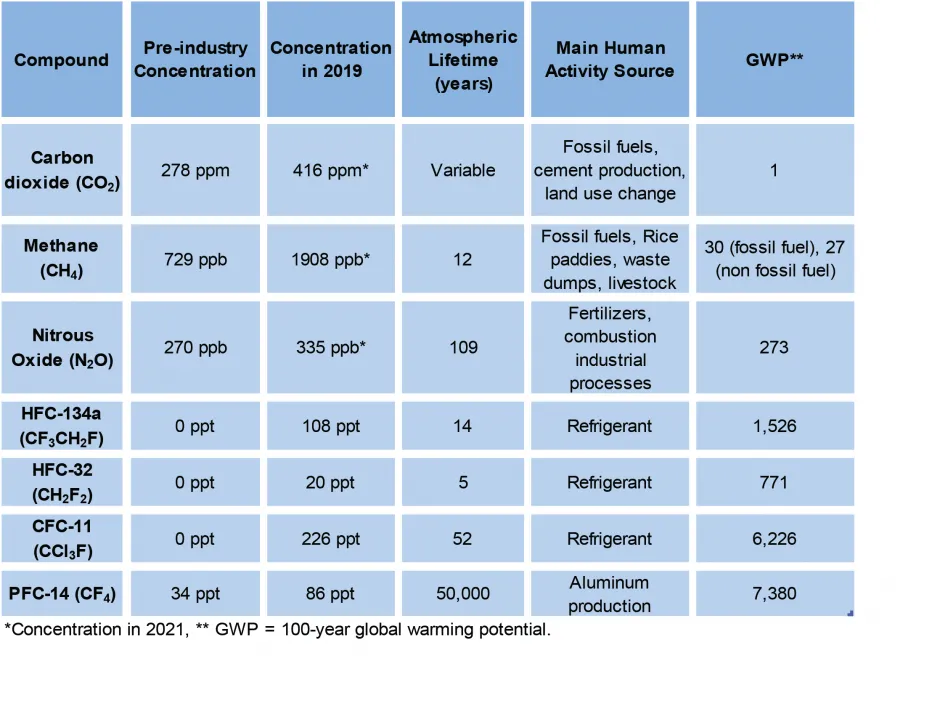

- Global Warming Potentials (GWPs) indicate the relative effectiveness of GHGs in trapping the Earth’s heat over a certain time horizon. CO2 is used as the reference gas and has a GWP of one.1 For example, the 100-year GWP of nitrous oxide (N2O) is 273, indicating that its radiative effect on a mass basis is 273 times that of CO2 over the same time horizon.1

- GHG emissions are discussed in terms of mass of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e), which are calculated by multiplying the mass of emissions by the GWP of the gas.5

The Main Greenhouse Gases1,2

Image

Atmospheric Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Since 1750, atmospheric concentrations of CO2, CH4, and N2O increased by 149%, 262%, and 124%, respectively, to levels that are unprecedented in the past 800,000 years.1,2

- Before the Industrial Revolution, the concentration of CO2 remained around 290 parts per million (ppm) by volume.1 In January 2023, the global monthly average concentration increased to 419.31 ppm, which is about 2.1 ppm higher than in 2022.6

Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Anthropogenic CO2 is emitted primarily from fossil fuel combustion. Iron and steel production, cement production, and natural gas systems are other significant sources of CO2 emissions.5

- The U.S. oil and gas industry emits 2.3% of its gross natural gas production annually, equivalent to 13 million metric tons (Mt) of methane— nearly 60 percent higher than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates.7

- CH4 and N2O are emitted from both natural and anthropogenic sources. Domestic livestock, landfills, and natural gas systems are the primary anthropogenic sources of CH4. Agricultural soil management (fertilizer) contributes 75% of anthropogenic N2O. Other significant sources include mobile and stationary combustion and wastewater treatment.5

- Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are the fastest growing category of GHG and are used in refrigeration, cooling, and as solvents in place of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).8

Emissions and Trends

Global

- In 2019, total global anthropogenic GHG emissions were 51.7 Gt CO2e. Since 1990, annual anthropogenic GHG emissions increased by 57%.9

- Average annual GHG emissions were 56 Gt CO2e from 2010-2019. This is the highest decadal average on record and almost 10 Gt CO2e more than the previous decade (2000-2009).4

- Emissions from fossil fuel combustion are a majority (73%) of global anthropogenic GHG emissions.10 In 2021, global emissions of CO2 from energy use totaled 35.3 Gt CO2.11

- From 2000 to 2021, global CO2 emissions from energy use increased 45%.11

- Since 2005, China has been the world’s largest source of anthropogenic CO2 emissions, surpassing the U.S.11

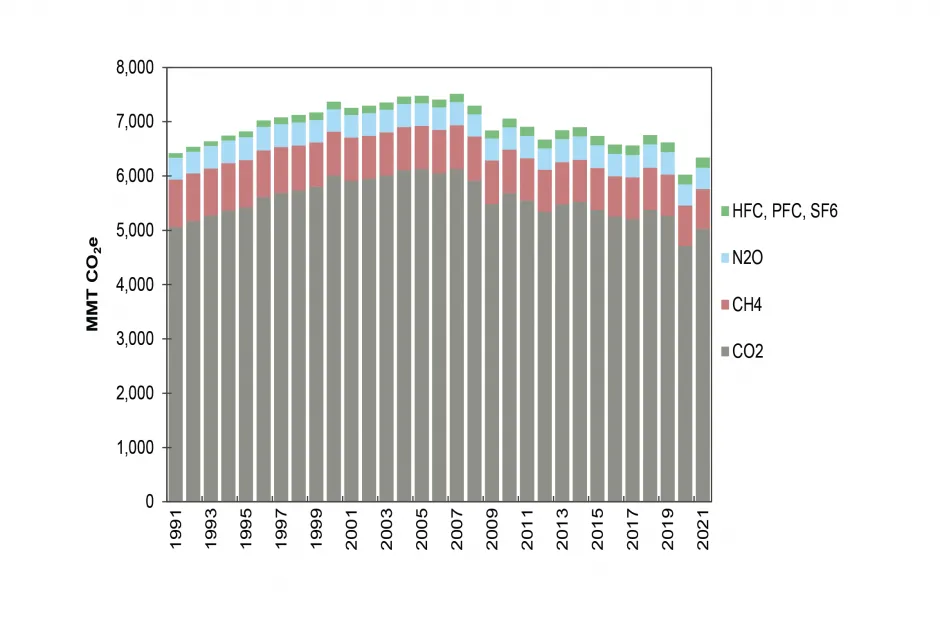

United States

- The U.S. represents less than 5% of the world’s total population, but was responsible for 13.5% of total anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2021.12,13

- GHG emissions in 2021 were 2.1% lower than in 1990, with an average annual decline rate of 0.02 percent.5

- Fossil fuel combustion is the largest source of U.S. GHGs, 73% of total emissions. Since 1990, fossil fuel consumption has decreased at a rate of 0.06%. However, both GHG emissions and fossil fuel consumption have decreased since 2005 by 15% and 19% respectively, while GDP kept growing.5

- CO2 emissions accounted for 79.4% of total U.S. GWP-weighted emissions (CO2e) in 2021, 1.7% lower than in 1990 and 17.9% lower than in 2005.5

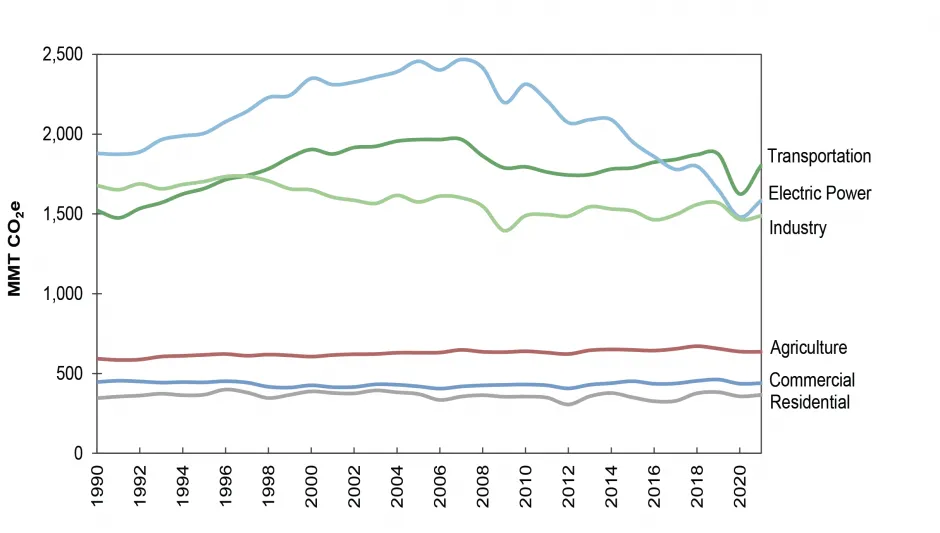

- The electric power industry produces 25% of total U.S. GHG emissions. Emissions from this sector have decreased 16% since 1990 and 36% since 2005.5

- Transportation is the largest contributor of U.S. GHG emissions, responsible for 28% of total emissions in 2021, (19% higher than in 1990 and 8% lower than 2005). Passenger cars and light-duty trucks accounted for 374 and 672 Mt CO2e, respectively, together making up 58% of U.S. transportation emissions and 16% of total U.S. emissions.5

- Urban sprawl, increased travel demand, population growth, and low fuel prices drive the growth of transportation GHG emissions.5

- Land use and forestry in the U.S. sequester CO2 in growing plants and trees, removing 12% of the GHGs emitted by the U.S. in 2021.5

- As a result of 2008 federal legislation, sources that emit over 25,000 metric tons (t) of CO2e are required to report emissions to the U.S. EPA.14

U.S. GHG Emissions by Gas5

Image

U.S. GHG Emissions by Sector5

Image

Emissions by Activity

Image

Future Scenarios and Targets

- Stabilizing global temperatures and limiting the effects of climate change require more than just slowing the growth rate of emissions; they require absolute emissions reduction to net-zero or net-negative levels.17

- Based on current trends, global energy-related CO2 emissions are anticipated to increase by 25% from 2020 to 2050.18

- Non-OECD countries’ CO₂ emissions are expected to grow by 1.0% annually, while OECD countries’ emissions are expected to grow by 0.2% annually. Despite this difference, OECD countries will still have per capita emissions 2.2 times higher than non-OECD countries in 2050.18

- Under the Kyoto Protocol, developed countries agreed to reduce their GHG emissions on average by 5% below 1990 levels by 2012. When the first commitment period ended, the Protocol was amended for a second commitment period with a new overall reduction goal of 18% below 1990 levels by 2020.19

- In 2015, UNFCCC parties came to an agreement in Paris with a goal to limit global temperature rise to less than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, in order to avoid the worst effects of climate change.20

- Global CO2 emissions would need to decline 48% from 2019 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero by around 2050 followed by net negative CO2 emissions to avoid temperature rise beyond 1.5° C.21

| 1 Teragram (Tg) = 1000 Giga grams (Gg) = 1 million metric tons (Mt) = 0.001 Giga tons (Gt) = 2.2 billion pounds (lbs) |

Cite As

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2023. "Greenhouse Gases Factsheet." Pub. No. CSS05-21.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2021) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Masson-Delmotte,V., et al.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- World Meteorological Organization (2022) WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin.

- IPCC (2007) Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Eds. S. Solomon, et al.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- IPCC (2022) Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. P.R. Shukla, et al. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2023) Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2021.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (2023) “Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide.”

- Alvarez, R., et al (2018) “Assessment of methane emissions from the U.S. oil and gas supply chain.” Science, 361: 186-188.

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (2021) “Short-lived Climate Pollutants.”

- PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (2022) Trends in Global CO2 and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (2021) Trends in Global CO2 and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2023) International Emissions by Fuel.

- U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (2023) The World Factbook.

- Andrew, R.M. and Peters, G.P. (2022) The Global Carbon Project’s fossil CO2 emissions dataset.

- U.S. EPA (2022) Learn About the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP).

- U.S. EPA (2023) “Emissions & Generation Resource Integrated Database (eGRID) 2021.

- U.S. EPA (2022) The 2022 EPA Automotive Trends Report.

- IPCC (2018) Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 C.

- U.S. EIA (2021) International Energy Outlook 2021.

- UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2021) “What is the Kyoto Protocol?”

- UNFCCC (2021) “Paris Agreement.”

- IPCC (2023) Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Summary for Policymakers.