U.S. Water Supply and Distribution Factsheet

Patterns of Use

All life on Earth depends on water. Human uses include drinking, bathing, crop irrigation, electricity generation, and industrial activity. For some of these uses, the available water requires treatment prior to use. Over the last century, the primary goals of water treatment have remained the same—to produce water that is biologically and chemically safe, appealing to consumers, and non-corrosive and non-scaling. The problems and solutions to maintaining water supply vary significantly by region. Failure by the government to enforce drinking water regulations and promptly protect public health resulted in lead contamination and cases of Legionnaires’ disease in Flint, MI.1 The arid southwest faces droughts, and decreasing water levels at the U.S.’s largest reservoirs Lake Powell and Lake Mead are impacting hydropower production.2 In marine systems such as south Florida, increased fresh water demand has led to the use of desalination plants.3

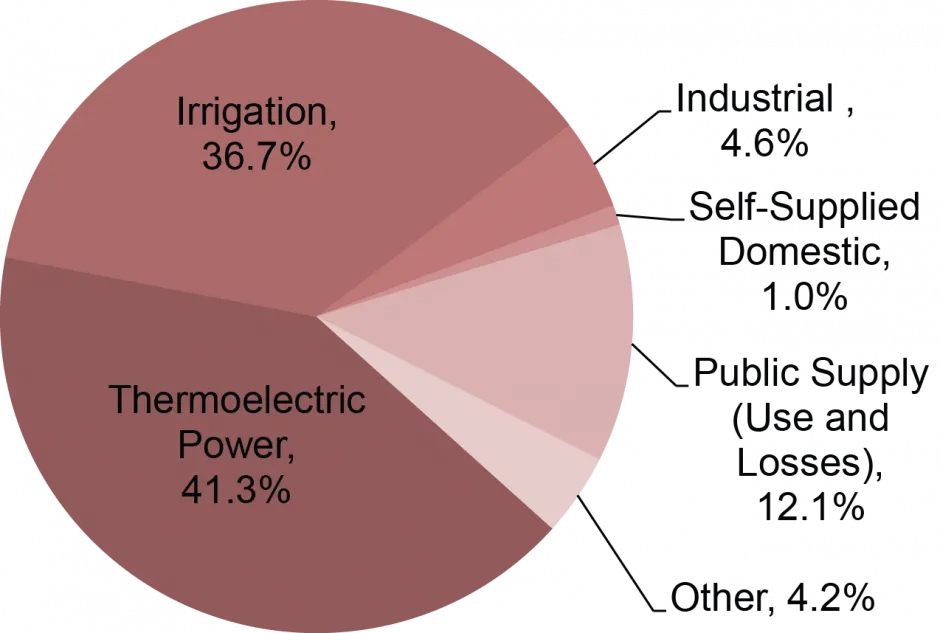

Water Uses

- In 2015, total U.S. water use was approximately 322 billion gallons per day (Bgal/d), 87% of which was freshwater. Thermoelectric power (133 Bgal/d) and irrigation (118 Bgal/d) accounted for the largest withdrawals.4 Thermoelectric power plants use water for cooling. Though 41% of daily water use is for power generation, only 3% of these withdrawals are consumptive.4 Irrigation includes water applied to agricultural crops along with the water used for landscaping, golf courses, parks, etc.4

- In 2015, California and Texas accounted for 16% of U.S. water withdrawals.4 These states along with Idaho, Florida, Arkansas, New York, Illinois, Colorado, North Carolina, Michigan, Montana, and Nebraska account for more than 50% of U.S. withdrawals.4 Florida, New York, and Maryland accounted for 50% of saline water withdrawals.4

Estimated Uses of Water, 20154

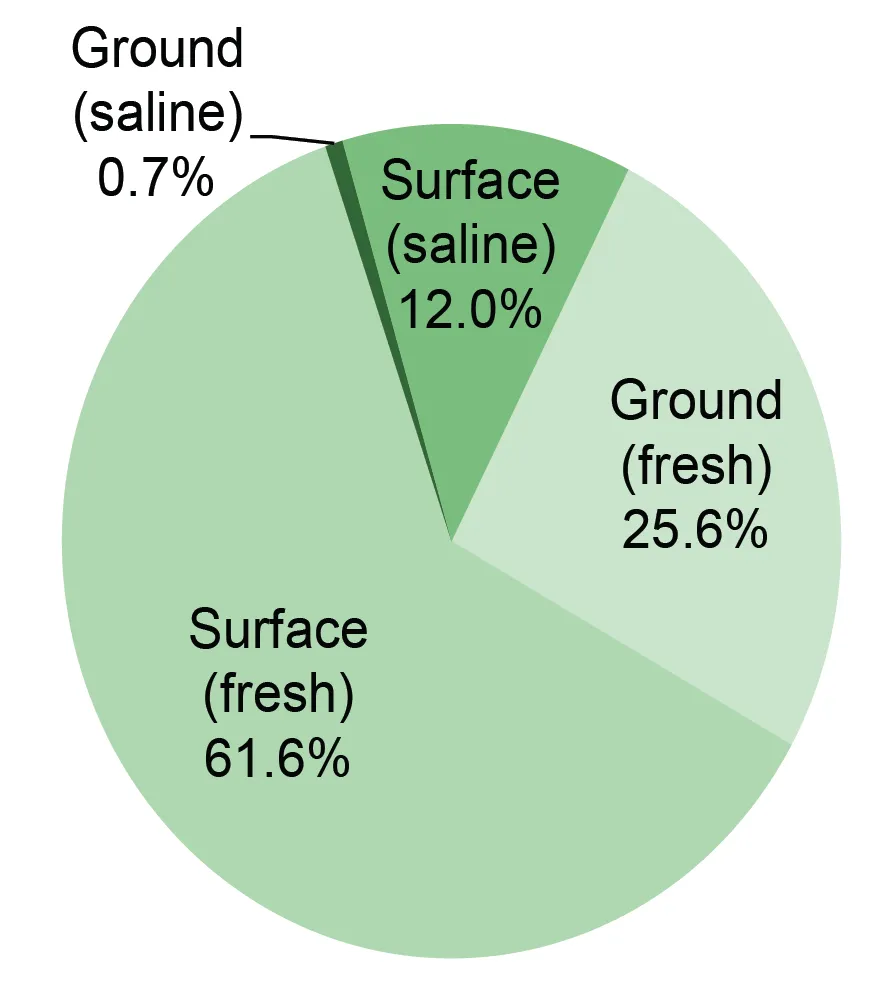

Sources of Water

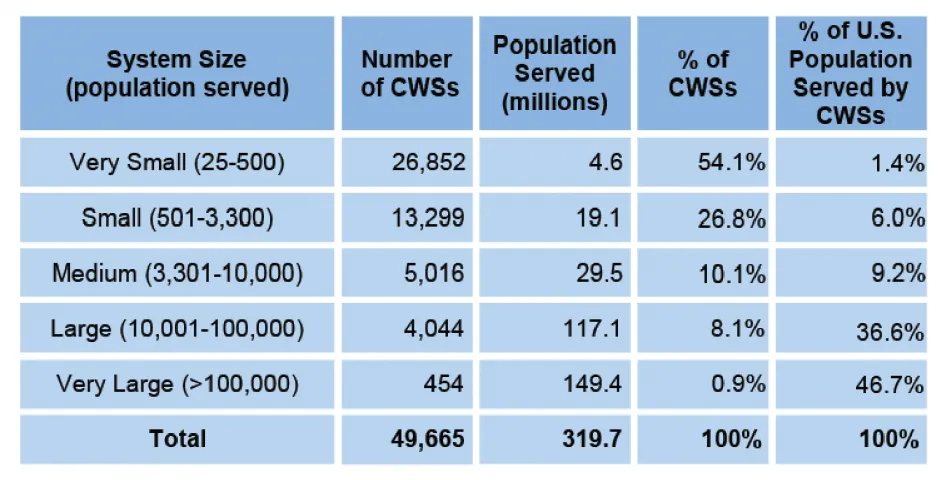

- Approximately 87% of the U.S. population relied on public water supply in 2015; the remainder rely on water from domestic wells.4

- Surface sources account for 74% of all water withdrawals.4

- In 2010, annual U.S. water withdrawal measured 1,543 m³ per person.5

- Approximately 152,548 publicly owned water systems provide piped water for human consumption in 2022, of which roughly 50,000 (33%) are community water systems (CWSs). Of all CWSs, 9% provide water to 83% of the population.6

- In 2006, CWSs delivered an average of 96,000 gallons per year to each residential connection and 797,000 gallons per year to non-residential connections.7

Sources of Water Withdrawals, 20154

Energy Consumption

- Two percent of total U.S. electricity use goes towards pumping and treating water and wastewater, a 52% increase in electricity use since 1996.8 Cities, on average, use 3,300-3,600 kWh/million gallons of water delivered and treated. Electricity use accounts for around 80% of municipal water processing and distribution costs.9

- Groundwater supply from public sources requires 2,100 kWh/million gallons, about 31% more electricity than surface water supply, mainly due to higher water pumping requirements for groundwater systems.8

- The California State Water Project is the largest single user of energy in California, consuming between 6-9.5 billion kWh per year, partially offset by its own hydroelectric generation. In the process of delivering water from the San Francisco Bay-Delta to Southern California, the project uses 3%-4% of all electricity consumed in the state.10,11

Water Treatment

- The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), enacted in 1974 and amended in 1986, 1996, and 2018, regulates contaminants in public water supplies, provides funding for infrastructure projects, protects sources of drinking water, and promotes the capacity of water systems to comply with SDWA regulations.12

- Typical parameters that the U.S. EPA uses to monitor the quality of drinking water include: microorganisms, disinfectants, radionuclides, organic and inorganic compounds.13

- Ninety-one percent of CWSs are designed to disinfect water, 23% are designed to remove or sequester iron, 13% are designed to remove or sequester manganese, and 21% are designed for corrosion control.7

- Use the Municipal Drinking Water Database to learn more about the drinking water systems of over 2,000 U.S. cities and the communities that they serve.14

Size Categories of Community Water Systems6

Life Cycle Impacts

Infrastructure Requirements

- The 2023 Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment found that U.S. water systems need $625 billion of investment by 2041 to continue providing clean safe drinking water.15

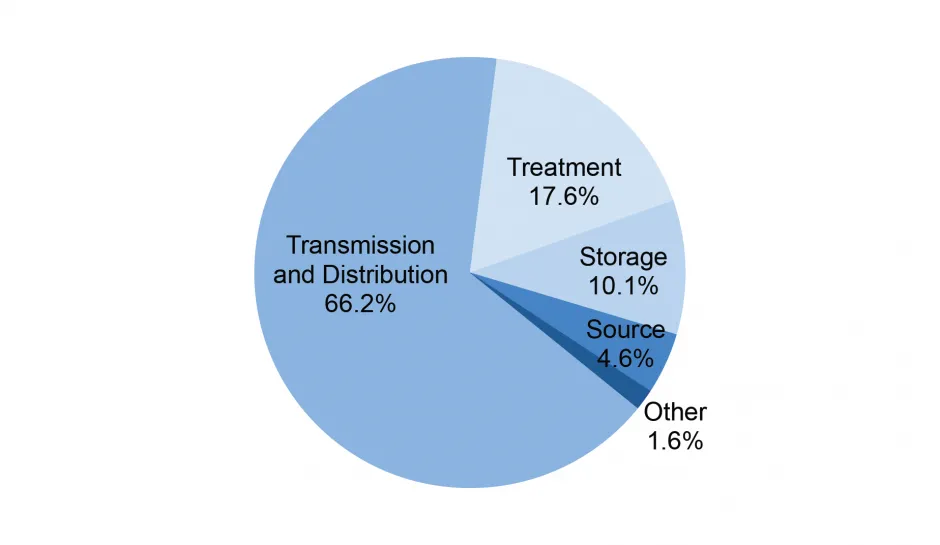

- The total national investment need for transmission and distribution is $420.8 billion. The other needs include treatment ($106.4 billion), storage ($55.3 billion), source development ($24.9 billion), and other systems ($17.6 billion).15

- Water systems maintain more than 2.2 million miles of transmission and distribution mains.16 In 2020, the average age of water pipes in the U.S. was 45 years old -- an increase in average age from 25 years old in 1970.17 Each year, 250,000 to 300,000 main breaks occur in the U.S., disrupting supply and risking contamination of drinking water.18

Drinking Water Need by 2041, by Project Type5

Electricity Requirements

- Supplying fresh water to public agencies required about 39 billion kWh of electricity in 2011, which increased by 39% beyond the 1996 values, mostly due to population growth and expansion of treatment facilities. This trend will likely continue in the coming years.8

- Household appliances contribute greatly to the energy burden. Dishwashers, showers, and faucets require 0.312 kWh/gallon, 0.143 kWh/gallon, and 0.139 kWh/gallon, respectively.20

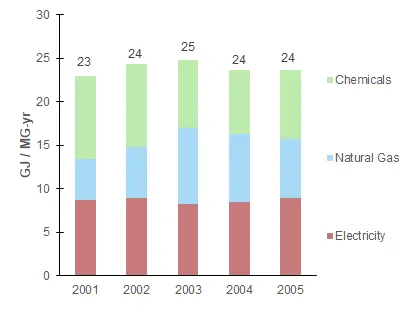

Life Cycle Energy Use for Ann Arbor Water Treatment Plant19

Consumptive Use

- Consumptive use is an activity that draws water from a source within a basin and returns only a portion or none of the withdrawn water to the basin. The water might have been lost to evaporation, incorporated into a product such as a beverage and shipped out of the basin, or transpired into the atmosphere through the natural action of plants and leaves.4

- Agriculture accounts for the largest loss of water (80-90% of total U.S. consumptive water use).21 Of the 118 Bgal/d freshwater withdrawn for irrigation, over half is lost to consumptive use.4

- Over the past 50 years, the consumption of water has tripled. With at least 40 states anticipating water shortages by 2024, the need to conserve water is critical.22

Solutions and Sustainable Alternatives

Supply Side

- Periodic rehabilitation, repair, and replacement of water distribution infrastructure would help improve water quality and avoid leaks.16

- Right-sizing, upgrading to energy efficient equipment, and monitoring and control systems can optimize systems for the communities they serve, and save energy and water in the process.9

- Significant energy efficiency improvement opportunities include pumps and motors.23

- Achieve on-site energy and chemical use efficiency to minimize the life cycle environmental impacts related to the production of energy and chemicals used in the treatment and distribution process.

- Reduce chemical use for treatment and sludge disposal by efficient process design, recycling of sludge, and recovery and reuse of chemicals.

- Generate energy on-site with renewable sources such as solar and wind.24

- Effective watershed management plans to protect source water are often more cost-effective and environmentally sound than treating contaminated water. For example, NYC chose to invest between $1-1.5 billion in a watershed protection project to improve the water quality in the Catskill/Delaware watershed rather than construct a new filtration plant at a capital cost of $6-8 billion.25

- Less than 4% of U.S. freshwater comes from brackish or saltwater, though this segment is growing. Desalination technology, such as reverse osmosis membrane filtering, unlocks large resources, but more research is needed to lower costs, energy use, and environmental impacts.8

Demand Side

- Better engineering practices:

- Plumbing fixtures to reduce water consumption, e.g., high-efficiency toilets, low-flow showerheads, and faucet aerators.26

- Water reuse and recycling, e.g., graywater systems and rain barrels.27

- Efficient landscape irrigation practices.27

- Better planning and management practices:

- Pricing and retrofit programs, proper leak detection and metering, residential water audit programs and public education programs.26,27

- Communities experiencing environmental injustice can use environmental justice toolkits, such as the Water Justice Toolkit.28

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2023. "U.S. Water Supply and Distribution Factsheet." Pub. No. CSS05-17.

References

- Flint Water Advisory Task Force (2016) Final Report.

- Udall, B., J. Overpeck (2017) The twenty-first century Colorado River hot drought and implications for the future.

- South Florida Water Management District (2021) “Desalination.”

- Dieter, C., et al. (2018) Estimated use of water in the United States in 2015. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1441.

- Our World in Data (2018) Water Use and Stress: Water withdrawals per capita.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2023) Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) Inventory Summary Report.

- U.S. EPA (2009) 2006 Community Water System Survey.

- Electric Power Research Institute (2013) Electricity Use and Management in the Municipal Water Supply and Wastewater Industries.

- Congressional Research Service (2017) “Energy-Water Nexus: The Water Sector’s Energy Use.”

- California Department of Water Resources (2020) Producing and Consuming Power.

- California Energy Commission (2020) Water-Energy Bank.

- Congressional Research Service (2021) Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) A Summary of the Act and Its Major Requirements.

- U.S. EPA (2021) “National Primary Drinking Water Regulations.”

- Hughes, Sara; Kirchhoff, Christine; Conedera, Katelynn; Friedman, Mirit, 2023, “The Municipal Drinking Water Database, 2000-2018 [United States]”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DFB6NG, Harvard Dataverse, V2.

- U.S. EPA (2023) Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment – Seventh Factsheet.

- U.S. EPA (2018) Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment – Sixth Report.

- Water Finance and Management (2017) “Bluefield: CAPEX for Pipe Suppliers to Hit $300 Billion Over Next Decade.”

- American Society of Civil Engineers (2021) 2021 Report Card For Americas Infrastructure.

- Tripathi, M. (2007) Life-Cycle Energy and Emissions for Municipal Water and Wastewater Services: Case-Studies of Treatment Plants in US

- Abdallah, A. and D. Rosenberg (2014) Heterogeneous Residential Water and Energy Linkages and Implications for Conservation and Management. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management, 140(3): 288-297.

- The National Agricultural Law Center (2013) “Water Law: An Overview.”

- EPA (2023) Water Conservation at EPA.

- U.S. EPA (2013) Strategies for Saving Energy at Public Water Systems.

- U.S. EPA (2021) “Energy Efficiency for Water Utilities.”

- Chichilnisky, G. and G. Heal (1998) Economic returns from the biosphere. Nature, 391: 629-630.

- U.S. EPA (2012) “How to conserve water and use it efficiently.”

- U.S. EPA (2020) “Water Management Plans and Best Practices at EPA.”

- American Rivers (2021) Water Justice Toolkit: A Guide to Address Environmental Inequities in Frontline Communities.