Autonomous Vehicles Factsheet

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) use technology to partially or entirely replace the human driver in navigating a vehicle from an origin to a destination while avoiding road hazards and responding to traffic conditions.1 The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has developed a widely-adopted classification system with six levels based on the level of human intervention. The U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) uses this classification system.2

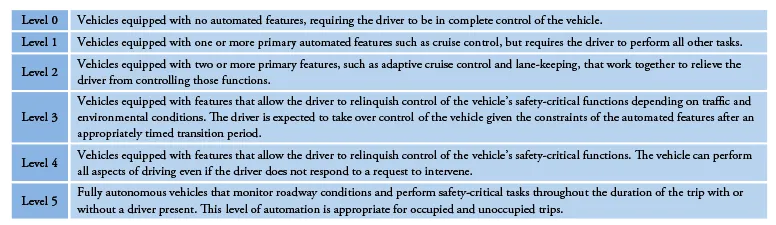

Levels of Automation

The SAE AV classification system is broken down by level of automation:2,3

Development of Autonomous Vehicles

AV research started in the 1980s when universities began working on two types of AVs: one that required roadway infrastructure and one that did not.1 The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has held “grand challenges” testing the performance of AVs on a 150-mile off-road course.1 No vehicles successfully finished the 2004 Grand Challenge, but five completed the course in 2005.1 In 2007, six teams finished the third DARPA challenge, which consisted of a 60-mile course navigating an urban environment obeying normal traffic laws.1 In 2015, the University of Michigan built Mcity, the first testing facility built for autonomous vehicles. Research is conducted there into the safety, efficiency, accessibility, and commercial viability of AVs.4 Unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), or drones, are being deployed for commercial ventures such as last-mile package delivery, medical supply transportation, and inspection of critical infrastructure.5

Autonomous Vehicle Technologies

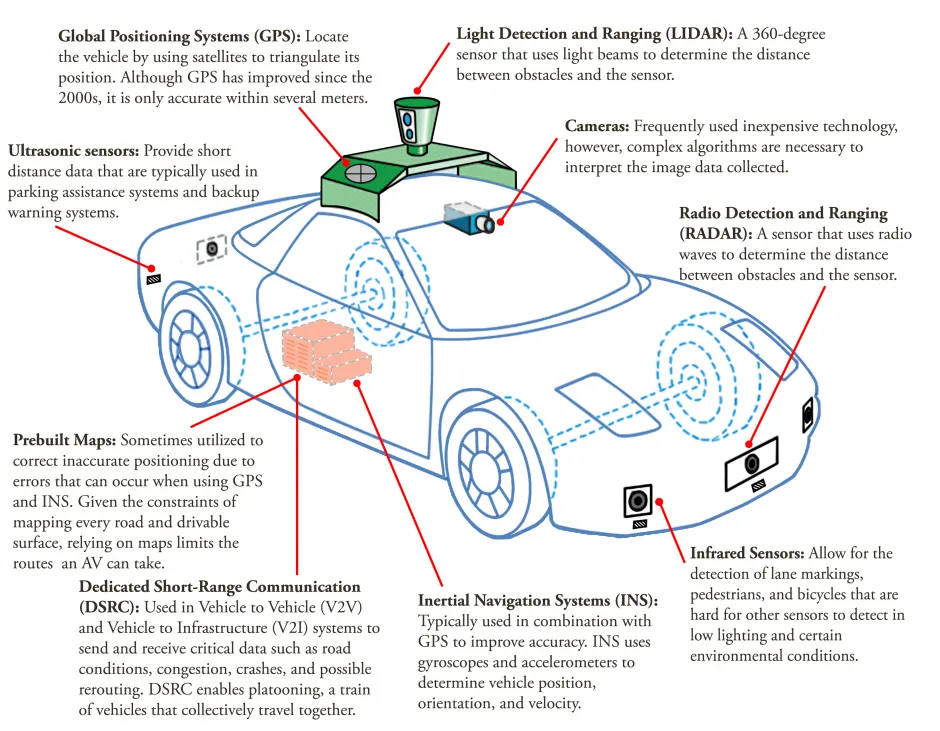

AVs use combinations of technologies and sensors to sense the roadway, other vehicles, and objects on and along the roadway.6

Autonomous Vehicle Technologies1,7,8,9

Current and Projected Market

Market Leaders

- Waymo has tested its vehicles by driving over 20 million miles on public roads and tens of billions of miles in simulation.10

- Teslas have driven over 3 billion miles in Autopilot mode since 2014.11

- Other major contributors include Audi, BMW, Daimler, GM, Nissan, Volvo, Bosch, Continental, Mobileye, Valeo, Velodyne, Nvidia, Ford, as well as many other OEMs and technology companies.6,12

Regulations, Liability, and Projected Timeline

- Regulation will directly impact the adoption of AVs. There are no national standards or guidelines for AVs, allowing states to determine their own.13 In 2018, Congress worked to pass the AV Start Act that would have implemented a framework for the testing, regulating, and deploying of AVs. The legislation failed to pass both houses.14 As of February 2020, 29 states and D.C. have enacted legislation regarding the definition of AVs, their usage, and liability, among other topics.15

- Product liability laws need to assign liability properly when AV crashes occur, as highlighted by the May 2016 Tesla Model S fatality. Liability will depend on multiple factors, especially whether the vehicle was being operated appropriately to its level of automation.16,17

- Although many researchers, OEMs, and industry experts have different projected timelines for AV market penetration and full adoption, the majority predict Level 5 AVs around 2030.18,19

Current Limitations and Barriers

- There are several limitations and barriers that could impede adoption of AVs, including: the need for sufficient consumer demand, assurance of data security, protection against cyberattacks, regulations compatible with driverless operation, resolved liability laws, societal attitude and behavior change regarding distrust and subsequent resistance to AV use, and the development of economically viable AV technologies.6

- Weather can adversely affect sensor performance on AVs, potentially impeding adoption. Ford recognized this barrier and started conducting AV testing in the snow in 2016 at the University of Michigan’s Mcity testing facility, utilizing technologies suited for poor weather conditions.12

Impacts, Solutions, and Sustainability

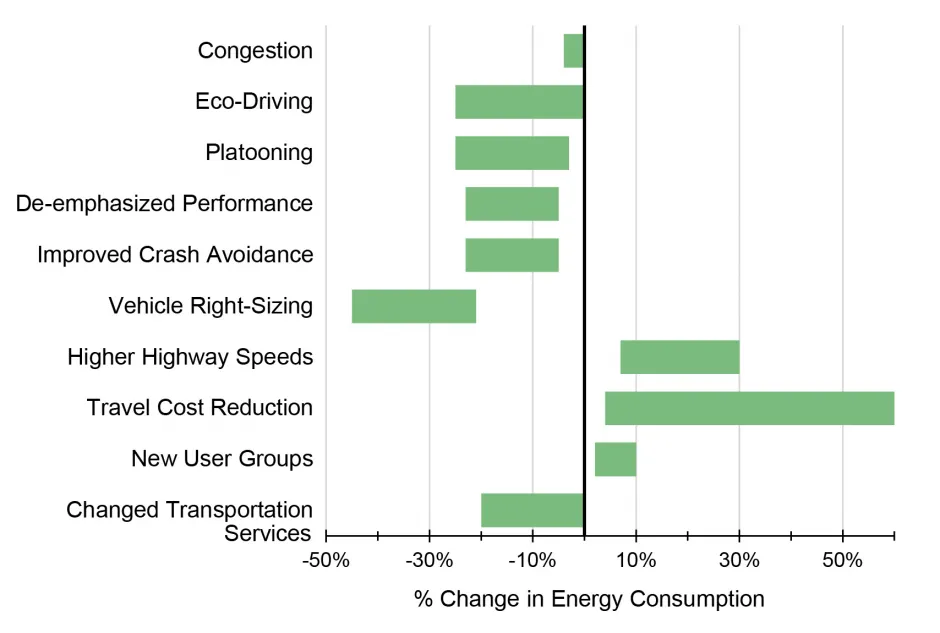

Although AVs alone are unlikely to have significant direct impacts on energy consumption and GHG emissions, when AVs are effectively paired with other technologies and new transportation models, significant indirect and synergistic effects on economics, the environment, and society are possible.20,21 One study found that when eco-driving, platooning, intersection connectivity and faster highway speeds are considered as direct effects of connected and automated vehicles, energy use and GHG emissions can be reduced by 9%.22

Metrics and Associated Impacts

- Congestion: Congestion is predicted to decrease, reducing fuel consumption by 0-4%. However, decreased congestion is likely to lead to increased vehicle-miles traveled (VMT), limiting the fuel consumption benefit.20

- Eco-Driving: Eco-Driving, a set of practices that reduce fuel consumption, are predicted to reduce energy consumption by up to 20%. However, if AV algorithms do not prioritize efficiency, fuel efficiency may actually decrease.20,23

- Platooning: Platooning, a train of detached vehicles that collectively travel closely together, is expected to reduce energy consumption between 3-25% depending on the number of vehicles, their separation, and vehicle characteristics.20

- De-emphasized Performance: Vehicle performance, such as fast acceleration, is likely to become de-emphasized when comfort and productivity become travel priorities, potentially leading to a 5-23% reduction in fuel consumption.20

- Improved Crash Avoidance: Due to the increased safety features of AVs, crashes are less likely to occur, allowing for the reduction of vehicle weight and size, decreasing fuel consumption between 5-23%.20

- Vehicle Right-Sizing: The ability to match the utility of a vehicle to a given need. Vehicle right-sizing has the potential to decrease energy consumption between 21-45%, though the full benefits are only likely when paired with a ride-sharing on-demand model.20

- Higher Highway Speeds: Increased highway speeds are likely due to improved safety, increasing fuel consumption by 7-30%.20,24

- Travel Cost Reduction: AVs are predicted to reduce the cost of travel due to decreased insurance cost and cost of time due to improvements in productivity and driving comfort. These benefits could result in increased travel potentially increasing energy consumption by 4% to 60%.20

- New User Groups: AVs are likely to increase VMT, especially for elderly and disabled users, and fuel consumption from new users by 2-10%.20

- Changed Mobility Services: Ride-sharing on-demand business models are likely to utilize AVs due to the significant reduction of labor costs.25 The adoption of a ride-sharing model is estimated to reduce energy consumption by 0-20%.20

- Although an accurate assessment of these interconnected impacts cannot currently be made, one study evaluated the potential impacts of four scenarios, each with unknown likelihoods. The most optimistic scenario projected a 40% decrease in total road transport energy and the most pessimistic scenario projected a 105% increase in total road transport energy.20

Projected Fuel Consumption Impact Ranges20,24

Potential Benefits and Costs

- In 2021, U.S. annual vehicular fatality rate was 42,915; 94% of crashes are due to human error. AVs have the potential to remove/reduce human error and decrease deaths.26,27 AVs have the potential to reduce crashes by 90%, potentially saving approximately $190 billion per year.28

- Potential benefits include improvements in safety and public health; increased productivity, quality of life, mobility, accessibility, and travel, especially for the disabled and elderly; reduction of energy use, environmental impacts, congestion, and public and private costs associated with transportation; and increased adoption of car sharing.1,13,29,30

- Potential costs include increased congestion, VMT, urban sprawl, total time spent traveling, and upfront costs of private car ownership leading to social equity issues; usage impact on other modes of transportation; and increased concern with security, safety, and public health.1,13,24,30,31

Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2023. "Autonomous Vehicles Factsheet." Pub. No. CSS16-18.

References

- Anderson, J., et al. (2016) Autonomous Vehicle Technology: A Guide for Policymakers. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA.

- Society of Automotive Engineers (2021) Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) (2018) Automated Vehicles 3.0 Preparing for the Future of Transportation.

- University of Michigan (2019) MCity Test Facility.

- Federal Aviation Administration (2020) Fact Sheet – The UAS Integration Pilot Program.

- Mosquet, X., et al. (2015) Revolution in the Driver’s Seat: The Road to Autonomous Vehicles.

- Adapted from The Economist (2013) How does a self-driving car work?

- Pedro, F. and U. Nunes (2012) Platooning with dsrc-based ivc-enabled autonomous vehicles- Adding infrared communications for ivc reliability improvement. Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), IEEE.

- Bergenhem, C., et al. (2012) Overview of Platooning Systems. Proceedings of the 19th ITS World Congress, Oct 22-26, Vienna, Austria.

- CNET (2020) Waymo Driverless Cars Have Driven 20 Million Miles On Public Roads.

- Electrek (2020) Tesla Drops A Bunch Of New Autopilot Data, 3 Billion Miles And More.

- Ford (2016) “Ford Conducts Industry-First Snow Tests of Autonomous Vehicles--Further Accelerating Development Program.”

- Fagnant, D., and K. Kockelman (2015) Preparing a nation for autonomous vehicles: Opportunities, barriers and policy recommendations. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 77, 167-181.

- The National Law Review (2019) Autonomous Vehicle Federal Regulation

- National Conference of State Legislatures (2020) Autonomous Vehicles.

- Gurney, J. (2013) Sue my car not me: Products liability and accidents involving autonomous vehicles.” Journal of Law, Technology & Policy, 2(2013): 247-277.

- Tesla (2016) A Tragic Loss. Blog.

- PWC (2015) Connected Car Study 2015: Racing ahead with autonomous cars and digital innovation.

- Underwood, S. (2014) Automated, Connected, and Electric Vehicle Systems: Expert Forecast and Roadmap for Sustainable Transportation.

- Wadud, Z. et al. (2016) “Help or hindrance? The travel, energy and carbon impacts of highly automated vehicles.” Transportation Research Part A 86: 1-18.

- Keoleian, G., et al. (2016) Road Map of Autonomous Vehicle Service Deployment Priorities in Ann Arbor. CSS16-21.

- Gawron, J., et al. (2018) “Life Cycle Assessment of Connected and Automated Vehicles: Sensing and Computing Subsystem and Vehicle Level Effects.” Environmental Science & Technology 52(5):3249–3256.

- Mersky, A. and C. Samaras (2016) “Fuel economy testing of autonomous vehicles.” Transportation Research Part C 65: 31-48.

- Brown, A., et al. (2014) “An analysis of possible energy impacts of automated vehicle.” Road Vehicle Automation. Springer International Publishing: 137-153.

- Burns, L., et al. (2013) Transforming Personal Mobility. The Earth Institute Columbia University.

- NHTSA (2022) Traffic Safety Facts.

- NHTSA (2018) Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey.

- Bertoncello, M. and D. Wee (2015) Ten ways autonomous driving could redefine the automotive world. McKinsey & Company.

- Cordts, Paige, et al. (2021) “Mobility challenges and perceptions of autonomous vehicles for individuals with physical disabilities.” Disability and health journal 14.4 (2021): 101131.

- Howard, D. and D. Dai (2014) Public Perceptions of Self-Driving Cars: The Case of Berkeley, California.

- Taiebat, M., et al. (2019) “Forecasting the Impact of Connected and Automated Vehicles on Energy Use: A Microeconomic Study of Induced Travel and Energy Rebound.” Applied Energy 247: 297-308